Off to the cinema to see Barbie and

Oppenheimer on the same day. I've

already written about Oppenheimer, but what about Barbie? What

about Barbie? What about Quake II? What about Barbie? What about Quake II? What about Quake II. What about Quake II.

Let's have a look at Quake II. Let's have a look at Quake II, because it has

been remastered and I'll get round to Barbie eventually. What

about Quake II? What is Quake II? Is it actually Quake 2?

No, it's Quake II. The logo is a stylised Q with two tails. The downwards part of the letter Q is called a tail. That's what it's called. That's the official word for the downwards part of the letter Q. Quake II is a first-person shooter, initially released for the PC

back in 1997. Developed by Id Software of Texas as a successor to the

technically innovative Quake, which came out the year before. The

pace of triple-A game development was much faster back then. For a while Quake II was a thing. It was the next big step in the evolution of the first person shooter, although it wasn't quite as large a step as Quake. Nonetheless it was, for a while, the top game in the top genre on what was briefly the most interesting gaming platform if not the most popular. It was a thing. Id Software were, for a while, kings of the world.

A couple of years later it was ported to the Nintendo N64 and original PlayStation, but you really had to play it on the PC to get the full effect. You really had to play it on the PC in 1997, because within a few years it was overshadowed by other games, because the pace of triple-A game development was etc. My recollection is that for much of the

decade that followed Quake II fell into a kind of semi-obscurity. It was yesterday's news. Obsolete. But over the last few years it has made a comeback, and in August 2023 it was re-released in remastered form for all the major gaming platforms, including the Nintendo Switch.

Technically this is the second go at remastering Quake II. The

first attempt came out in 2005, as a free bonus for people who bought the disc-based

version of Quake 4, but it was only available for the XBox 360. Because Quake 4 was

one of the XBox 360's launch titles, that's why. And it was only available for a short while, because Quake 4 wasn't very popular, and within a few years the rights to

the series were bought from Activision by Bethesda, who

re-released the game without any bonuses. The original remaster was essentially the

original Quake II ported for the XBox 360, minus the expansion

packs, with no special extras, but on a technical level

it was apparently really good.

My hunch is that it would have attracted more attention if it had been released in the second half of the 2000s. In 2005 Quake II's unsubtle shooty-shooty

action was cheesy, but in the wake of the heavily-scripted, quasi-realistic military shooters that emerged in the late

2000s its simplicity would have been a refreshing change. In 2019 NVidia used the game as

a showcase for the real-time raytracing capability of their RTX graphics

cards, although Quake II RTX was really a source port, not

a remaster. It replaced the original game engine but the level data was the

same. In fact you were supposed to supply the levels yourself.

Now, I'm old enough to remember Quake and Quake II when they were new. I

remember being disappointed with Quake, but in

2021 Bethesda remastered it, and I finally realised how wrong I was. I wrote about it last year. I liked it! The remaster preserved the original game's slam-bang action and terrific soundtrack, but it also added a mass of extras, including a pair of

really good new expansions, plus a clutch of excellent user-made levels. It

even included mouse and keyboard support on consoles. I played it on my

PlayStation 4 and enjoyed it immensely. I have no idea how well it sold, but

it made the Quake franchise hip again.

Did the remaster of Quake II hit me the same way? No. The

Quake remaster had "Dimension of the Machine", a set of huge,

good-looking maps that pushed the Quake engine to its limits. In

contrast the new campaign for Quake II, "Call of the Machine", is hit

and miss, and often feels like an admittedly well-made late-90s expansion

pack. Overall the remaster doesn't have the same amount of new content, although apparently a

port of the original PlayStation version is planned as a free update. For some

reason mouse and keyboard support on consoles is half-baked. The engine

recognises the hardware, even the mouse's scroll wheel, but there's no option to change mouse scaling or

even reverse the Y-axis of the mouse so it's unusable.

The fundamental problem is that Quake II is fundamentally... it's fundamentally competent. It's decent. But uninspiring and occasionally lacklustre. Within eighteen months it felt like the final evolution of a dead end. The original Quake was short and

sweet. Each level was an uncomplicated burst of adrenaline.

Quake II has a more complicated mapping system whereby the

player can revisit earlier levels, but in order to show this off the developers

made the player backtrack through a bunch of visually nondescript industrial

corridors. It has an inventory system, but that just means that the tough battles are easy, because the player can pop some power-up pills whenever they feel like it.

And the maps rely on ambush after ambush after ambush. On a visual level Quake II is much less monotonous than

Quake, but it doesn't have much of a visual identity, and my

recollection is that within a few months it was completely overshadowed as a technological showcase by

Unreal, which was just as boring to play but looked great.

And of course within a year both Quake II and

Unreal were overshadowed by Half-Life, which had all the

exciting gunplay and action of Quake II but added an engaging

single-player storyline and a clever AI system. It had a refreshing air of

verisimilitude that separated it from purely sci-fi shooters with

their electronic laser guns and purple skies etc. And then a year later it was

overshadowed yet again by the multiplayer-focused Quake III and Unreal Tournament, which reverted to the uncomplicated

action of Quake but with bots that were fun to play against even in single-player mode. On a personal

level I loved Unreal Tournament to bits, even though I have

never, ever played a multiplayer match.

To this day none of these people have ever worn pants.

Engine Wars

Bit of backstory. Id Software was founded in Texas, the United States, in the

early 1990s. The company specialised in action-packed PC games

at a time when PC games tended to be slow-paced, cerebral titles such as

Ultima and

Microsoft Flight Simulator and

Space Quest and

Lotus 123 which wasn't a game etc. On a technical level the PC had a lot of latent power, but it didn't

have the custom graphics hardware of dedicated games consoles, so it was crap at

Street Fighter.

But Id were coding wizards, and Commander Keen (1990-1991) was a

perfectly fine Super Mario clone that outdid the

Mario games in some respects; it was fast and smooth on PC

hardware that should, by rights, have been unable to cope with it. Until just now I hadn't realised that the entire

Commander Keen series was released over the course of just a

single year, from December 1990 to December 1991. And then just five months

later Id released Wolfenstein 3D. Everything was quicker back then.

Gods lounged on the riverbank. They dipped their fingers in the water and pulled out chunks of gold.

Wolfenstein 3D made people take notice of Id, but the company

really hit the spot with Doom, which came out in 1993.

Doom was a fast-paced 3D action game with a clever engine that

used a bunch of tricks to run quickly on relatively weak hardware. The baddies

were two-dimensional cardboard cutouts that were scaled up and down in order to

imitate perspective. The level geometry was made of flat, two-dimensional maps

extruded upwards, which meant that the engine couldn't render multi-storey

buildings or anything that involved putting one sector on top of another. But

unlike Wolfenstein it could render different ceiling heights,

different light levels, angled walls, a textured floor, and in general it was

far more versatile.

It is done

The Doom engine - retrospectively called Id Tech 1 - could

generate large, monster-packed levels with a mixture of indoors and outdoors

environments that didn't require a loading pause whenever the player went

inside a building, and it could do so on a bog-standard 486. I remember being

impressed back in 1993 with the indoors-and-outdoors aspect. Very few 3D games

allowed the player to look through a window into the world outside. It

sounds like a simple thing, but a few games are

still like that today, e.g. Fallout and The Long Dark. The

indoors and outdoors are treated as separate spaces. That wasn't the case with

Doom. Each map was a single, seamless whole.

The Doom engine was flexible and easy to hack, and within a few

years the nascent World Wide Web was awash with user-made levels, some of

which were better than the original maps. But the engine had limitations. Apart

from the fundamentally two-dimensional nature of the geometry, Doom's

levels were static. There were no landslips, no collapsing buildings, no

toppling trees. Everything was fixed. Competitors such as

Duke Nukem 3D and Dark Forces had rudimentary

scripting, but Doom only had simple trigger lines that could open

doors. The engine couldn't generate sloped surfaces, dynamic

lights, coloured lights, atmospheric effects, variable gravity, portals, fog,

etc. Monster AI was very simple. The maps were easy to edit but the rest of

the game was monolithic, without the modularity of modern engines.

It was fast, though, and it could throw monsters at the player like nobody's

business. Some of the larger, player-made maps for modern source ports, such

as Deus Vult and the Spire levels, have literally

thousands of monsters.

There's still a decently large Doom mapping community today. It must be one of the longest-lived online communities. The earliest

user-made levels hosted by Doomworld date from 1994 (the very

first, by a chap called Jeffrey Bird, was released in April of that year). Not

many gaming communities can trace their lineage back to 1994.

Did I mention

that Doom almost single-handedly transformed the PC from

spreadsheets and point-and-click adventures to mainstream hip gaming platform?

Kids suddenly wanted a PC so they could play Doom. Which was awkward

because a decent PC cost over a thousand pounds back then. Not cheap. But

Doom was seductive, and without it the PC gaming scene would be

very different today and probably much smaller and not as good.

After the release of

Doom II Id Software got to work on a successor. An elaborate role-playing game that would revolutionise PC gaming once again. But this created a problem. One faction within

Id, led by John Romero, wanted to have dragons and character classes and an

inventory, but after working hard on the engine for two years the majority of

the developers just wanted to get the game finished. In fact a similar thing had happened with

Doom. The game had an elaborate design document,

the Doom Bible, but it was almost entirely ignored by the development team, because after labouring on the engine for months none of the team wanted to spend extra time coding realistic chairs and character classes etc.

Along similar lines Id pared

Quake down into an exercise in minimalism, an action game

that didn't even have a use button. In retrospect this was one of Id's things. All of their projects, right up to

Rage in 2011, began with a complicated storyline and role-playing elements, but ended up sacrificing everything in favour of clever technology. I mention

Rage because the game was infamous for its spartan story, and also for being Id's first real flop. The problem is that by 2011 the gaming public expected more than just a slick engine with clever texture streaming. The gaming public wanted a story with engaging characters, and

Rage did not deliver.

I played it a few years ago and enjoyed it, but only because it was £2.99. At £45.99 I would have been bitterly disappointed.

But still, towards the end of the development of Quake the role-playing faction were either fired or asked to leave, depending on

who you ask. They took with them some of Id's eccentricity and sense of fun,

although in Id's defence the company survives to this day while John Romero's

Ion Storm only lasted a few years.

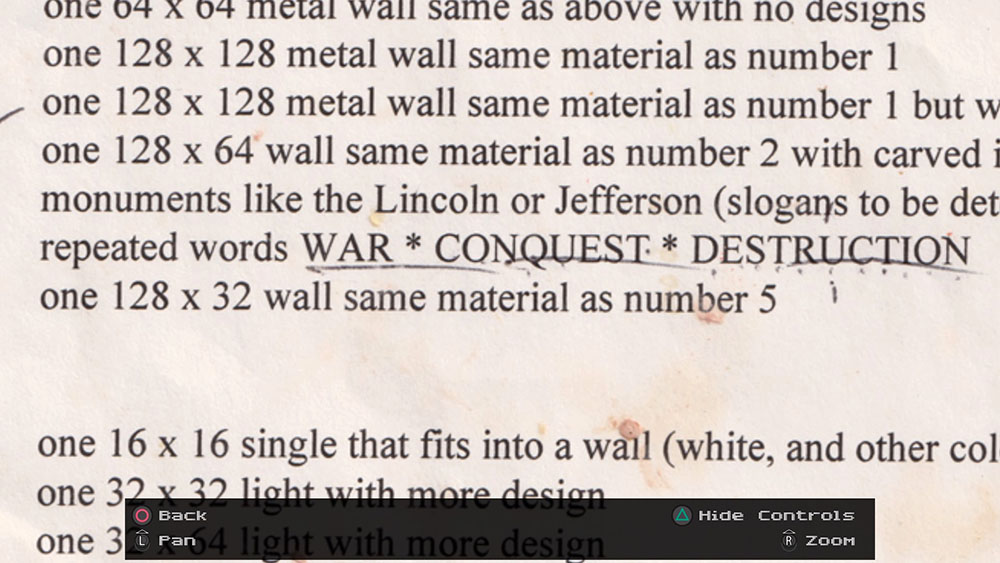

This is the secret developer's room at the end of Quake 2. Pictured on

the right is Donna Jackson, who joined Id Software as office manager in

1993 and as of 2019 still worked at the company. Along with Tim Willits

she's one of a tiny handful of old-school Id employees who was still

around to appear in the credits of the 2016 Doom reboot.

I remember being unmoved by Quake. It had none of the zany,

anything-goes tone of Duke Nukem 3D, and despite the clever engine the

gameplay felt simplistic and the environments were monotonous. On a visual

level it was drab, with a colour palette that infamously consisted of brown,

dark purple, yellow, and dark green. The technology was clever but in gameplay terms it didn't feel like an advance on Doom.

On the positive side the engine could

render proper 3D geometry, essentially any arbitrary collection of 3D shapes,

as long as those shapes didn't have curves:

And the monsters were polygons as well, so they no longer looked like

cardboard cutouts:

But the engine ran slowly on anything less than a fast Pentium, so Id was

forced to use a lot of level design tricks to lower the polygon count. In

particular the levels tended to be small, cramped dungeons, with none of the

indoors-outdoors aspect of Doom. Instead of large-scale monster fights

the maps had ambushes of two or three monsters at a time, and to make the

fights feel substantial the player's weapons were unusually weak, which had

the effect of stretching out fights and making them feel like a slog.

Ironically for a game that later became famous for fast-paced deathmatches

and Quake Done Quick, the original

single-player Quake was, in 1996, slow and dull.

Quake ended up being remembered more as a framework than a game,

firstly as an engine for multiplayer deathmatch and secondly as one of the

first 3D gaming engines that was licensed to third parties. It was nowhere

near as popular as later iterations of Id Tech, or for that matter the

contemporary Build engine, but it did form the base on which Valve Software's Half-Life was made. Half-Life used a heavily-modified version of

the original Quake engine, tweaked so extensively that the news it

was built on Quake rather than Quake II came as a

surprise to many (it surprised me, anyway).

Part of the reason for Quake's tepid response as an engine is that it

was just slightly pre-modern. It predated a bunch of things that

became standard in first-person shooters later on. It was a DOS application,

so there was no plug-and-play; the player had to configure the controls, sound

card, and video card manually, perhaps even the mouse driver. The development tools were obtuse, and this being 1996 there was nowhere near the wealth of online support that is available for modern gaming engines.

I remember playing Quake initially with keyboard control, because

mouse+keys wasn't one of the standard control options, or at least mouselook

wasn't a standard option. You had to fiddle with the development console to

get it working. And Quake didn't initially have support for 3D

graphics cards. It ran in grainy 320x200-pixel software mode. 3D graphics

cards were cutting-edge at the time and DOS games needed specially-written

drivers to take advantage of them.

I mention all this because Quake II feels "normal" in comparison. It belongs to the modern age. Its predecessors were quirky and weird

in one way or another, whereas Quake II was designed to run under

Windows, with support for DirectDraw, with out-of-the-box support for 3D

graphics cards - OpenGL, 3DFx Glide, and PowerVR - and native mouselook. With

a bit of work the original executable will run on Windows 10. The game had software rendering, but it marked the point where software rendering became an afterthought, not the main rendering engine.

How did Quake II come about? Id wanted to

make a next-generation first-person shooter with better technology and more

vibrant colours than Quake, but when they came to give it a name all of

their choices had been used up, so it became Quake II. Beyond the name

there was no continuity with the original. The only thing carried forward was the quad damage power-up.

There was an initial attempt to make a

complicated game with RPG elements, but the team gave up on that idea

early on. Traces of it remain. There's an almost entirely useless silencer

power-up that quietens the player's shots for a brief period, plus a vestigial

stealth system. Enemies who are unaware of the player's presence receive extra

damage, but beyond a handful of scripted encounters the

baddies generally spot the player first. The player is free to move from one

level to the next and back, but there's never a compelling reason to do so.

On a tonal level Quake owed a lot to Se7en,

The Crow, Neil Gaiman's Sandman comics, The Crow etc. It was goth-y and

mysterious, with a dark ambient soundtrack by Nine Inch Nails. Occasionally turgid and overwrought. In

contrast Quake II was red-blooded, motorcycle-riding rock and

roll action, with a soundtrack made up of electronic speed metal.

There's the germ of a university essay there. Quake's oppressive

visuals and nightmarish soundtrack evoked the uncertain, destablised, post-Cold War, post-recession early-to-mid-1990s

alternative nation movement, while Quake II embodied the bullish confidence of the latter part of the 1990s, a period

when it was perfectly normal to own a civilian Humvee and care deeply about tech IPOs. This might be one of the reasons Quake II fell into

obscurity in the 2000s. It was the nu-metal Quake. No-one wanted to swim with nu-metal in the late 2000s. People still do not want to swim with nu-metal.

The Game

As mentioned up the page I enjoyed

Quake II in 1997, but not wholeheartedly. After the

first few levels the maps blended into one another and there was an awful lot of

backtracking through similar-looking sci-fi environments. Despite the vibrant

colour scheme Quake II has a curiously generic, characterless

look. The sound design is excellent, but the monsters are often crude-looking robot puppets. And of course

within a few months Unreal's reflective floors, procedurally-generated

water, volumetric fog, light bloom etc made Quake II look staid.

A quarter of a century later Quake II still has the same problems,

and playing the remaster again I still found myself getting bored in the

second half of the game. I remember blowing up a big gun, and being impressed

with the skybox, but I can't remember how I got there. Despite the existence of 3D graphics accelerators Id still faced the

issue of getting the game to work on limited hardware. Whereas

Quake had a lot of cramped corridors Quake II generally has much larger - or at least taller - indoors sections, and at least on a few occasions the game tries to give a sense of scale, but the

gameplay still consists mostly of close-range ambushes. I lost count of the amount of times I fired a grenade around a corner and was rewarded with a monster damage sound.

As with the spartan storyline this is something else that dogged Id all the way throughout its life. Doom 3 and Rage also had ambushes, and again this became untenable by the time of Rage, because the gaming public wanted more than just repetitive ambushes in tight corridors. I mean, yes, the Call of Duty-style games that were popular in the early 2010s also had scripted ambushes, but they also had tank levels, jet levels, AC-130 levels, story levels, the occasionally wide open battlefield. Rage had cars, but the game did very little with them.

But let's talk about Quake II. The remaster tweaks the game a bit. Some of the maps have been modified,

although I don't remember enough of the later levels to comment on the differences. This part of

the first level is however new, on the right, underneath the covered walkway:

Or was it in the multiplayer maps? I don't know. The slicy-stabby-metal "trespasser" baddy now has a new attack whereby he

smashes the ground and sends the player flying, which is alarming at first. It

doesn't hurt much, but if you aren't careful it can hurl you into lava. It was

apparently coded for the original game but commented out. I'm not sure why. The between-level progress reports have been remade, and the intro movie has at the very least been upscaled.

I played through all of Quake II and then had a go at the

expansions. I've read bad things about them, but "The Reckoning" is okay. It's

concise and feels just like an extension of the main game. It adds a couple of

new weapons - they look like designs from Unreal - and as with the base game it devolves into backtracking and ambushes, but it's fundamentally decent. Rogue Software's "Ground Zero" is more elaborate and has

a bunch of new baddies, but I didn't like it as much. It goes on and on and

on until it becomes a slog.

At the time it was infamous for having tiny, hard-to-hit gun turrets that slowed the action down, but the remaster makes

the turrets weaker and adds a laser tracking beam so that they're more

obvious. But they still turn the game into an irritating stop-start affair and I was glad to get the

expansion over with.

The new progress screens look like this. Is that a typo?

The real meat is the new set of maps, "Call of the Machine", which are

structured with a hub-and-spoke model. The player flies down from a mothership

in orbit, as in Doom Eternal, and completes a series of small

mini-episodes.

The expansion is a mixed bag. The new levels look great, but they very rarely

have the scale of "Dimension of the Machine" from the Quake remaster. The screenshot at the top is an exception, but for some reason none of the other maps ran with that idea. There's something conservative about

them. They often feel like good late-1990s user-make Quake II maps, which is nice, but I expected something epochal, something monumental. Each episode has a secret level that usually involves some kind of

mass-carnage gauntlet, but I didn't find them particularly challenging, and the reward is generally just more ammo.

Wait, what?

The hub level.

It's good to have the new episode, and the hub level looks great, and

I enjoyed it, but I doubt I'll ever replay it.

Anything else? The PlayStation 4 version has a bunch of graphical options.

Back in 1997 everybody played it on the PC with a 3D graphics card, but I

remember feeling that software mode looked crisper, because it didn't have

texture smoothing. The PS4 version has an option to turn off texture

smoothing, which I picked. It also has CRT simulation, anti-aliasing, and

updated models.

With and without texture smoothing. I prefer the crude-but-crisp look at

the bottom to the smooth-but-smushy look at the top.

There are a bunch of extras, including some early demo levels. The game

doesn't go out of its way to advertise them, and I only stumbled on them while

exploring the menus. As far as I can tell they just have the level data, e.g.

they don't implement the early pre-release version of the

Quake II engine. Quake II was the first of Id's 3D shooters without a status bar face, although the team were

originally going to include one. The status bar face came back for

Quake III Arena and then went away again forever.

The Strogg were obviously modelled on [][][][] Germany. The German market is

touchy about the [][][][]s, which bit Id in the 1990s given that

Wolfenstein 3D had a bunch of [][][][] regalia and early versions

of Doom also had some [][][][] iconography. Let us not talk of the [][][][]s.

I haven't described the plot. Earth is under attack by aliens called The

Strogg, which is a generic science fiction name that Id picked in a

hurry because they had a deadline. You are a space marine. You are sent to

stop The Strogg, along with a bunch of other space marines, but this being

1997 all of your comrades immediately die, so you have to stop the Strogg

yourself. The world wasn't quite ready for squad-based combat yet. Quake II teases squad-based combat in the expansion packs, but every time you find some comrades they get killed before you can join up with them.

The Strogg are space aliens who dismember human beings and turn them into

cyborg monsters. On a tonal level Quake II is odd. The tortured

prisoners and body horror elements should be revolting, but the graphical

style and sound design is cartoonish enough that it comes across as comedy. In 1997 I wasn't sure whether I was supposed to find the prisoners funny or not, with

their overwrought cries of "make it stop" and "it hurts" and "kill me now", and I'm none the wiser today. I mean, as a gag you can turn on some of the Strogg torture machines, and when the prisoners die their bodies explode with a comedy squelching noise, and at one point you actually have to crush a crucified prisoner in order to get hold of a keycard, which isn't something you'd see in e.g. Animal Crossing.

I mention this because Quake was unsettling and completely

humourless, and both Quake 4 and Doom 3 played

things mostly straight, so in retrospect Quake II feels like...

well, it was the nu-metal Quake, the late-90s

Quake, the mountain-of-cocaine, we're-going-to-have-an-IPO

Quake.

Anything else? The console version has a weapons wheel that slows down time.

If you plug in a mouse the scroll wheel will scroll through a list of weapons,

but as mentioned earlier there isn't an option to reverse the Y-axis or

change the mouse sensitivity, so I used a controller instead. Beyond that Quake II is an excellent remaster of a seven-out-of-ten game with a good-but-not-excellent

bunch of extras that suffers from comparison with the remastered

Quake, which shone new light on a neglected masterpiece. The core game is solid first-person-shooter

junk food, but even in 1997 I remember feeling that it felt uninspired.

That's one of the reasons why Half-Life had such a huge

impact, a year later. It rethought the first-person-shooter genre and rebuilt

it from the ground up, with masses of polish and an engaging storyline. Quake II's monster AI was clever for 1997, with the baddies actively negotiating the maps to hunt the player and occasionally ducking the player's shots - they do that far more often in the remaster - but Half-Life took things to another level.

As such Quake II suffers from having neither the classic simplicity of the original game nor the

sophistication of the games that followed. It also suffers from the fact that Id was

starting to run out of ideas at the time. And every empire falls eventually. At the time of

Quake II and arguably Quake III Arena in 1999 Id was

one of the leading developers of first-person-shooters, but over the years the company's output slowed dramatically, and most of the original team left. The original Id essentially fizzled out with Rage, which nobody remembers today; by that time the Quake and Wolfenstein franchises had passed into the hands of other developers.

Hearteningly the 2016 reboot of Doom was a smash, and with the

success of Doom Eternal Id's future is assured, but

almost all of the people who worked on Quake and the original

Doom are gone, so it's really Id-in-name-only. But it does still

exist, there is that.