"...we came in?"

"...we came in?"Full four hundred thousand years ago Britain was cast from the world, when the ice that linked it to Europe melted. The country and its people subsequently developed in a non-standard way, and thus Stanley Unwin, and spanking, and the deep-fried chocolate bar, which is a chocolate bar that has been deep-fried and coated in

From this nexus arose a pair of games that are very obscure on the international scene, but are fondly remembered by British men of a certain age. Manic Miner was the first; Jet Set Willy, its sequel, was the second. Manic Miner in particular was one of the early killer apps for the ZX Spectrum, a home computer which dominated the British computing scene during the 1980s. It was the brainchild of Clive Sinclair, a British electronics enthusiast who had tried throughout the 1960s and 1970s to make a business out of electronic gadgets, initially miniature radios, and then pocket calculators and digital watches. They were often very clever examples of cost-cutting miniaturisation, and sold at keen prices, but they soon developed a reputation for shoddy build quality and months-long delivery delays. His company wasted a lot of money on a miniature CRT television that nobody wanted, and a combination of economic recession, faulty products, and competition from the Far East eventually did him in.

Sinclair had a knack of raising his business from the grave time and again. After the calculators and digital watches died a death he discovered the microcomputer, back when people still called them microcomputers. His machines used off-the-shelf components, and were originally sold in kit form; they were cheap, and that was important in the British market. Early efforts such as the ZX80 and ZX81 were barely more advanced than programmable calculators, although they sold well because there was a widespread perception that the computer revolution was the next big thing, and that Britain needed to transform or die, and furthermore the novelty of being able to type words onto the television was very powerful.

The ZX Spectrum of 1982 was far more impressive than Sinclair's earlier machines. A colour display, 48kb of memory in the posh model, an optional printer and mass storage, rubber keys rather than a touch-sensitive matrix, £175. It outsold the more expensive Commodore C64 handily, and for a few years Clive Sinclair seemed like the future of British industry. Although the machine flopped in the important US market he was knighted in 1983 and became Sir Clive. Almost immediately he fell back into his bad old ways, producing a string of unsuccessful products that culminated in the Sinclair C5, a wobbly plastic electric scooter that became a national joke. Sinclair was forced to sell his business off in 1986, and nowadays he is a champion poker player and member of high-IQ society MENSA who is famous for having his way with numerous women who are younger than him. He also designs electric bicycles that nobody buys and wears a shirt and tie all the time, like a one-man Gilbert & George. That's enough about Clive Sinclair. In the next section, which is a few lines down the page, I will talk about Manic Miner.

I would pay money to see Clive Sinclair do something on telly with Gilbert & George. They could call themselves Gilbert & George & Clive. I picture them in matching C5s, doing something both artistic and scientific.

(I originally wrote this with Hardcore Gaming 101 in mind, which explains the obsession with cataloguing different versions of the game, and the lengthy explanation of Britishness at the beginning.)

Manic Miner (Nineteen Eighty-Three)

It is impossible to separate Manic Miner from its author, eccentric loner genius Matthew Smith. British games writers of the period tended to fit into three basic groups. There were the former mainframe programmers and electrical engineers, such as Geoff Crammond and David Crane, who had decided to try their hand at games; these were serious men who produced serious games that involved physics. Then there was the next generation, the kids who grew up actually playing the games; like you or I they toyed with the idea of making their own games, but instead of giving up after writing a plot and designing a few sprites they did it. They were driven by a satanic lust for money, fame, and glory. Most of them ended up writing movie tie-ins for Ocean Software, or cheap BMX games for Codemasters.

And there were the crazed eccentrics, with wild hair and strange obsessions. Jeff Minter is the most famous of these. He loved llamas and yaks and he dressed like a hippie because he was a hippie. A new breed of electronic cyber-hippie. Still is. "Too weird to live, too rare to die." Matthew Smith was the other one. He dressed in normal people clothes - although he did not wear socks, as at least two contemporary interviews in different magazines pointed out - but had huge black hair that hid his face. He was a one-man software development team at a time when such a thing was still viable, and his games reflected his personality alone, his love of Monty Python and underground comics. Nowadays such people are confined to the world of indie games, or open source operating systems; in 1983 it was just possible for this band of loners to become a major force in the mainstream games industry - to shape it around themselves. Albeit that the industry was much smaller than today, and I am only talking about Britain.

Smith had an early start, having his first game published at the tender age of 16. It was a forgettable title called Styx, a little bit reminiscent of the 1980 arcade game Wizard of Wor. Although the gameplay was simplistic, it featured smooth sprite movement at a time when Spectrum games tended to flicker like mad. It had been submitted on spec to Liverpool-based Bug-Byte Software, and although it was only a modest success the company had enough faith in Smith to release his next title. He wrote Manic Miner over a period of eight weeks on a TRS-80, waking in the evening and coding straight until lunchtime the next day, at which point he crashed out until waking again.

The game was directly inspired by the arcade hit Donkey Kong, and by Miner 2049er, an Atari 800 title that had been written by Californian Bill Hogue. Matthew Smith had been a fan of Hogue's earlier TRS-80 games, and had learned most of his programming nous by disassembling his code. On the suggestion of Bug-Byte, Smith set out to make a game with a miner and some caves, and jumping, and at some point his imagination took over and added lethal toilets and falling Skylab space stations and Pac-Men with legs. Miner 2049er itself was never released for the Spectrum, which led to an urban legend amongst Spectrum owners that Smith's game was a direct copy; in reality the two were very different. 2049er was far closer to the fast-paced action of Space Panic and Donkey Kong, whereas Manic Miner placed much more of an emphasis on timing puzzles. Ultimately ZX Spectrum players had to wait until A'n'F's Chuckie Egg before they got a decent Miner 2049er clone.

The game was directly inspired by the arcade hit Donkey Kong, and by Miner 2049er, an Atari 800 title that had been written by Californian Bill Hogue. Matthew Smith had been a fan of Hogue's earlier TRS-80 games, and had learned most of his programming nous by disassembling his code. On the suggestion of Bug-Byte, Smith set out to make a game with a miner and some caves, and jumping, and at some point his imagination took over and added lethal toilets and falling Skylab space stations and Pac-Men with legs. Miner 2049er itself was never released for the Spectrum, which led to an urban legend amongst Spectrum owners that Smith's game was a direct copy; in reality the two were very different. 2049er was far closer to the fast-paced action of Space Panic and Donkey Kong, whereas Manic Miner placed much more of an emphasis on timing puzzles. Ultimately ZX Spectrum players had to wait until A'n'F's Chuckie Egg before they got a decent Miner 2049er clone.Manic Miner was released in September 1983 for the 48K ZX Spectrum, at a regular full price of £5.95. It attracted glowing reviews and was a big success, remaining in the charts for months afterwards whilst contemporary hits such as Jet Pac and Football Manager and Ant Attack rose and fell. The game earned Bug-Byte a lot of money, although Smith's contract ensured that he saw only a small percentage of this. As a result of this dissatisfaction - interviews imply that the company had been using creative accounting to hide the game's profits - Smith left Bug-Byte to set up a new software house with some veterans of the local software scene. He had been under a freelance contract for Bug-Byte when he wrote Manic Miner, with a clause that allowed him to withdraw the game from circulation on written request, at which point the rights would revert to him. In retrospect this was a terrible mistake on Bug-Byte's part, and from early 1984 onwards the rights to Manic Miner were transferred to Software Projects, Smith's new home. The two editions had a few graphical differences, and were sold with different cover paintings. Bug-Byte went bust a year later.

The basic gameplay is easy to describe. You play Miner Willy, who has stumbled on some underground caves, and your task is to collect a load of treasure and then escape. The cave complex is divided into twenty individual screens, each of which contains a number of treasures, and Willy can only progress to the next cave when he has collected all of them. Unfortunately the caves are guarded by monsters, and bushes, which are apparently poisonous. In fact anything that is not the ground or a piece of treasure is lethal. Furthermore Willy has a limited air supply in each cavern and cannot fall very far. The controls are very simple, just left and right and jump. This being 1983 Willy cannot be steered through the air, and thus the player has to make sure that he really wants to jump, because there is no going back once Willy is in the air. Too far gone. Ain't no way back.

The basic gameplay is easy to describe. You play Miner Willy, who has stumbled on some underground caves, and your task is to collect a load of treasure and then escape. The cave complex is divided into twenty individual screens, each of which contains a number of treasures, and Willy can only progress to the next cave when he has collected all of them. Unfortunately the caves are guarded by monsters, and bushes, which are apparently poisonous. In fact anything that is not the ground or a piece of treasure is lethal. Furthermore Willy has a limited air supply in each cavern and cannot fall very far. The controls are very simple, just left and right and jump. This being 1983 Willy cannot be steered through the air, and thus the player has to make sure that he really wants to jump, because there is no going back once Willy is in the air. Too far gone. Ain't no way back.On a technical level it built on the smooth movement of Styx. The graphics were bold and colourful and generally avoided the ZX Spectrum's colour mixing limitations, and the game had the novelty of a continuous soundtrack - a blippy version of Greig's "Hall of the Mountain King" that looped and looped and looped, in addition to a deranged and off-kilter version of "The Blue Danube" on the title screen. The game also had a proper ending, another novelty. The original release on Bug-Byte was accompanied by a competition, which was something of a fad for the period. The idea was that the first bunch of people to decipher the secret message on the last level were invited to a play-off in order to win a grand prize. The October 1983 edition of Computer & Video Games reveals that a man called Jim Wills was the first to perform this incredible feat. He won a colour television. The playoff was apparently scheduled for Christmas of that year, but I can find no record of it ever taking place; Matthew Smith left Bug-Byte around that time, taking the game with him, so perhaps it was quietly abandoned.

"What do points mean? Prizes!"

If this was a magazine, and not a blog, this paragraph would be in a little box alongside the main text. It would be a boxout. Instead it is in a little box inside the main text, which means that it is a box-in. Ah-ha-ha-ha.

Actual real physical prizes for winning a computer game were popular in the early 1980s. Domark's very first game, a multi-part (mostly) text adventure called Eureka! (1984), had a prize of twenty-five thousand pounds. Not a trinket or a trip to a theme park or anything clever, just twenty-five thousand pounds. Cold hard cash. Cheque, whatever. Other publishers were a bit more imaginative. The first person to beat Firebird's Gyron (1985) won a Porsche 924, one of the cheap mid-80s front-engined Porsches that you can't even give away on eBay nowadays. Automata's curious crossword-puzzle-of-a-game Pimania (1982) had a golden sundial worth £6,000. The clues were extraordinarily cryptic and the prize wasn't claimed until July 1985, by which time Automata had folded, although to the company's credit they handed over the sundial nonetheless. The epic Mike Singleton strategy wargame adventure thing Lords of Midnight (1984) had possibly the most bizarre prize of all; the idea was that the first person to win the game would have their campaign written up and published as a fantasy novel. Sadly this idea was scrapped although it seems ripe for rediscovery.

At this point Google tells me that Retro Gamer wrote an article on the exact same topic ages ago, so I'll stop. I learn that the prize for winning Kokotoni Wilf (1985), which I always thought had a stupid name and I haven't changed my opinion since, was to meet Lee Majors. One man claims to have actually won this prize, although it doesn't seem like the kind of prize you'd boast about, especially if you are a man, which that man is.

They don't mention Hareraiser, which sounds like a spoof of Hellraiser, although it came out in 1984, three years before the Clive Barker film. The prize was a golden pendant of a hare apparently worth £30,000, but therein lies a tale. The golden hare - the actual self-same golden hare - had previously been the prize for figuring out Kit Williams' illustrated book Masquerade in 1979. It had been buried somewhere in England, and readers were supposed to work out exactly where by solving a set of clues in the book. However the winner essentially stumbled on the prize by using a little bit of inside information and brute force. He then used the prize as collateral to fund a software house, Haresoft, for the express purpose of using the prize as a prize again. Having said that, there was an option of winning £30,000 in cash instead, in which case the hare might well have been sold off and then used as a prize yet again by somebody else.

And it was all nonsense. Whereas Gyron and Eureka! etc were entertaining to play even if you didn't care about winning the competition - Gyron was dead spooky, in fact - Hareraiser was basically a big clue with no gameplay value, which sold for £8.95. And you had to buy a second game, Hareraiser: Finale, in order to enter the competition. You were essentially spending almost £18 to enter a competition. It was a swizz anyway, because the clues in the two games didn't mean anything. The whole thing was essentially a cheap rip-off of Masquerade that didn't work. Very few people bought the games and nobody won the prize, which was eventually auctioned off at Sotheby's in order to pay off Haresoft's debts.

Still, it was a nice-looking hare. I mean, really nice. It's just the right side of gaudy and would not look out of place in a film. Kit Williams comes across as the kind of sincere, talented, hard-working creative type who was just born to be shafted.

Over in the States, Atari's Swordquest series was probably the most visible game-and-prize offering; the company planned to release four element-themed games between 1982 and 1984, with the prizes being four expensive fantasy trinkets (a pendant, a chalice etc), with the grand prize of a great big silver sword with a gold handle worth $50,000, which was a fair sum in those days. A bloody great sword!

A sword! The executives at Atari must have had an enormous cocaine habit. Sadly - thankfully for the winner's parents, sadly for the rest of us - the Great Video Game Crash of 1983 put the kibosh on the competition, and the last two games were never properly released. The final game was never even started, let alone finished, and rumour has it that the sword ended up in the possession of Atari's chief executive, who no doubt used it to dispose of unwanted staff when the Atari 5200 bombed.

A sword. I was going to say "wouldn't it be funny if one of those deer hunter games had a Winchester rifle as a prize", in jest, but there probably was a deer hunter game that had a rifle as a prize. At this point the boxout is becoming as long as the article, but that's okay. I like it in here, it's cosy. Nice and warm.

If this was a magazine, and not a blog, this paragraph would be in a little box alongside the main text. It would be a boxout. Instead it is in a little box inside the main text, which means that it is a box-in. Ah-ha-ha-ha.

Actual real physical prizes for winning a computer game were popular in the early 1980s. Domark's very first game, a multi-part (mostly) text adventure called Eureka! (1984), had a prize of twenty-five thousand pounds. Not a trinket or a trip to a theme park or anything clever, just twenty-five thousand pounds. Cold hard cash. Cheque, whatever. Other publishers were a bit more imaginative. The first person to beat Firebird's Gyron (1985) won a Porsche 924, one of the cheap mid-80s front-engined Porsches that you can't even give away on eBay nowadays. Automata's curious crossword-puzzle-of-a-game Pimania (1982) had a golden sundial worth £6,000. The clues were extraordinarily cryptic and the prize wasn't claimed until July 1985, by which time Automata had folded, although to the company's credit they handed over the sundial nonetheless. The epic Mike Singleton strategy wargame adventure thing Lords of Midnight (1984) had possibly the most bizarre prize of all; the idea was that the first person to win the game would have their campaign written up and published as a fantasy novel. Sadly this idea was scrapped although it seems ripe for rediscovery.

At this point Google tells me that Retro Gamer wrote an article on the exact same topic ages ago, so I'll stop. I learn that the prize for winning Kokotoni Wilf (1985), which I always thought had a stupid name and I haven't changed my opinion since, was to meet Lee Majors. One man claims to have actually won this prize, although it doesn't seem like the kind of prize you'd boast about, especially if you are a man, which that man is.

They don't mention Hareraiser, which sounds like a spoof of Hellraiser, although it came out in 1984, three years before the Clive Barker film. The prize was a golden pendant of a hare apparently worth £30,000, but therein lies a tale. The golden hare - the actual self-same golden hare - had previously been the prize for figuring out Kit Williams' illustrated book Masquerade in 1979. It had been buried somewhere in England, and readers were supposed to work out exactly where by solving a set of clues in the book. However the winner essentially stumbled on the prize by using a little bit of inside information and brute force. He then used the prize as collateral to fund a software house, Haresoft, for the express purpose of using the prize as a prize again. Having said that, there was an option of winning £30,000 in cash instead, in which case the hare might well have been sold off and then used as a prize yet again by somebody else.

And it was all nonsense. Whereas Gyron and Eureka! etc were entertaining to play even if you didn't care about winning the competition - Gyron was dead spooky, in fact - Hareraiser was basically a big clue with no gameplay value, which sold for £8.95. And you had to buy a second game, Hareraiser: Finale, in order to enter the competition. You were essentially spending almost £18 to enter a competition. It was a swizz anyway, because the clues in the two games didn't mean anything. The whole thing was essentially a cheap rip-off of Masquerade that didn't work. Very few people bought the games and nobody won the prize, which was eventually auctioned off at Sotheby's in order to pay off Haresoft's debts.

Still, it was a nice-looking hare. I mean, really nice. It's just the right side of gaudy and would not look out of place in a film. Kit Williams comes across as the kind of sincere, talented, hard-working creative type who was just born to be shafted.

Over in the States, Atari's Swordquest series was probably the most visible game-and-prize offering; the company planned to release four element-themed games between 1982 and 1984, with the prizes being four expensive fantasy trinkets (a pendant, a chalice etc), with the grand prize of a great big silver sword with a gold handle worth $50,000, which was a fair sum in those days. A bloody great sword!

A sword! The executives at Atari must have had an enormous cocaine habit. Sadly - thankfully for the winner's parents, sadly for the rest of us - the Great Video Game Crash of 1983 put the kibosh on the competition, and the last two games were never properly released. The final game was never even started, let alone finished, and rumour has it that the sword ended up in the possession of Atari's chief executive, who no doubt used it to dispose of unwanted staff when the Atari 5200 bombed.

A sword. I was going to say "wouldn't it be funny if one of those deer hunter games had a Winchester rifle as a prize", in jest, but there probably was a deer hunter game that had a rifle as a prize. At this point the boxout is becoming as long as the article, but that's okay. I like it in here, it's cosy. Nice and warm.

And that was the last I saw of Kim Cattrall. The boat pulled away, and then she was gone. Manic Miner is a notoriously difficult game. Although it belongs to the platform genre it bears few similarities to the evolved style of Mario and Sonic. Its gameplay is a lot less forgiving and a lot more rigid; it resembles an ultra-hard Mario ROM hack, a kind of prehistoric ancestor of Kaizo Mario World. There is usually only one way to complete each cavern, which must be carried out with a mixture of pixel-perfect jumping and split-second timing. Nowadays, with save states, this is frustrating but not impossible, but in 1983 there were no save states, and the player had to finish it in one sitting. The first few caverns were fairly simple - although the very first room had a couple of tricky jumps - but beyond level five or so the difficulty ramped up into Ghosts & Goblins territory, at least until the player had memorised each level's pattern, which required a tonne of playing time.

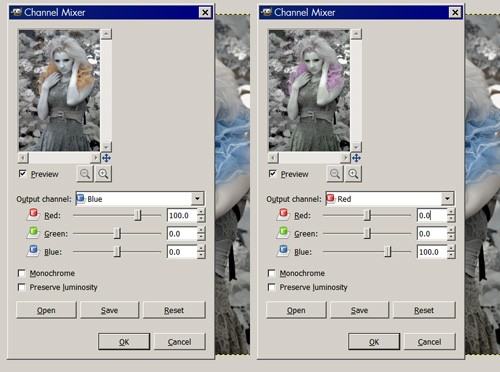

One of the slight differences between the Bug-Byte original (left) and the

One of the slight differences between the Bug-Byte original (left) and theSoftware Projects re-release (right). Some of the baddies are now

Penrose triangles, a shape adopted by Software Projects as their logo.

Is time measured in tonnes? An aeon, then. In addition to the soundtrack and the proper end, Manic Miner also threw in a number of gameplay elements that were still quite unusual in those halcyon days. The first screen had conveyor belts and collapsing platforms; level 14, the Skylab Landing Bay, forced the player to dodge Skylab space stations that fell from the top of the screen; level 19 featured a set of moving mirrors that reflected beams of light which sapped the player's air.

The game was pumped full of Smith's peculiar sense of humour. Level five featured a caricature of bespectacled former Bug-Byte executive Eugene Evans, whose lair was filled with lethal toilets that had been demanded by Smith's three-year-old brother. Levels eight and twelve featured an alien Kong Beast, a kind of green-skinned version of Donkey Kong who you could drop into a vat, although you didn't have to do this because Matthew Smith did not like violent computer games. Other levels featured hopping Pac-Men, and Ewoks from the hot new blockbuster film Return of the Jedi. The overall impression was of a game that had never in front of a committee, or indeed one that had not been near a lawyer (some later ports removed Kong).

Manic Miner was ported for almost all of the contemporary 8-bit machines that were sold in the UK, including such oddballs as the Oric 1 and Dragon 32. The Commodore C64 port was generally faithful, presented in a "windowboxed" format, although the graphics had a strangely washed-out look. There was also a Commodore C16 port that retained all of the levels, albeit in simplified form, which was impressive given that the game had never been released for the 16K version of the ZX Spectrum. Manic Miner was even ported for the 16-bit Commodore Amiga, in 1990, although this version received mixed reviews. The graphics were enlarged and Miner Willy grew a huge nose, but for some reason the designers chose to make the levels larger than the screen, so that the display had to scroll to keep the player in sight. There was also a port for the abortive early-90s Sam Coupé, an 8-bit machine released in 1989, during the heyday of the 16-bit machines; this was more faithful than the Amiga version, but the Coupé was a lost cause and so very few people got to play it. Outside the world of mobile phones the most recent port was a 2002 version for the Game Boy Advance, which combined the scrolling of the Amiga version with the enhanced speed of the Coupé port.

Manic Miner was ported for almost all of the contemporary 8-bit machines that were sold in the UK, including such oddballs as the Oric 1 and Dragon 32. The Commodore C64 port was generally faithful, presented in a "windowboxed" format, although the graphics had a strangely washed-out look. There was also a Commodore C16 port that retained all of the levels, albeit in simplified form, which was impressive given that the game had never been released for the 16K version of the ZX Spectrum. Manic Miner was even ported for the 16-bit Commodore Amiga, in 1990, although this version received mixed reviews. The graphics were enlarged and Miner Willy grew a huge nose, but for some reason the designers chose to make the levels larger than the screen, so that the display had to scroll to keep the player in sight. There was also a port for the abortive early-90s Sam Coupé, an 8-bit machine released in 1989, during the heyday of the 16-bit machines; this was more faithful than the Amiga version, but the Coupé was a lost cause and so very few people got to play it. Outside the world of mobile phones the most recent port was a 2002 version for the Game Boy Advance, which combined the scrolling of the Amiga version with the enhanced speed of the Coupé port.I'll be damned if I could find an Amiga disk image of the game, and although I finally got an Oric emulator to run - after spending ages trying to find the machine's ROM - I lost the will to live before managing to get a screenshot.

The game's simplicity lent itself to unofficial conversions and fan-made sequels. Top ZX Spectrum fan site World of Spectrum lists

Although Manic Miner is still fondly remembered, it was overshadowed by its sequel, Jet Set Willy, which preserved the same core gameplay but greatly expanded the playing area, and remains a towering achievement of the early British computing gaming scene...