Let's have a look at The Talos Principle, a puzzle game from 2014, which was the year of Jennifer Lawrence surrounded by flames. That's how I remember 2014. And 2015. They were the years of Jennifer Lawrence surrounded by flames, because London was covered with posters for The Hunger Games: Mockingjay and its sequel, The Hunger Games: Mockingjay. I miss those posters. It was only a few years ago but I feel nostalgic for those posters.

It was all different back then. Jennifer Lawrence was a thing. Electric cars were mostly crap. Snakes did not have breasts because XCOM 2 hadn't come out yet, and the thought of humanity being brought to its knees by a global pandemic was fanciful - unless you had played The Talos Principle, but I'll get to that. The game recently went on sale so I decided to check

it out.

Is it any good? Yes. It deserved all the award nominations it got. It didn't win anything because it was too left-field, but it deserved those nominations. Talos was made by Croteam, a Croatian development team famous for

the Serious Sam games, in which you blow up huge waves of baddies

in a series of visually attractive but mostly empty giant arenas. The

Sam games are cheerfully brainless -

Duke Nukem crossed with Smash TV - but The Talos Principle is a complete change of tack. It's a meditative puzzle game with a philosophical bent.

Chip's Challenge in 3D, with a story.

Purely as a puzzle game Talos is clever albeit occasionally

frustrating, but it also works as a story with an emotional core, which is

impressive given that the gameplay mostly consists of putting boxes on

pressure plates and looking through holes.

It takes place in the future. Decades,

centuries, possibly longer. We're all dead. A thaw in the arctic

permafrost unleashed an ancient virus that was lethal to primates, including

us. It was a slow-acting sleeping sickness with a lengthy gestation period, so

by the time the world's virologists woke up to the threat the virus was too

widespread to be contained.

There's an implication that the virus can survive indefinitely in the

natural environment, which means that the Earth is now permanently

inhospitable to primate life. Other animals are apparently okay, but the human

race is dead and gone, not to return on this day or any other day.

The orangutans are dead as well. What of the lemur? Probably dead. Most

of the historical record has been erased by the passage of time.

Sounds bleak, doesn't it? And yet the game is surprisingly hopeful. It turns

out that a group of human scientists came up with a plan to ensure that

something of humanity would survive. They proposed to create an artificial

intelligence that would inherit the Earth from us.

They didn't have the computing power to generate an artificial soul at the

time, so they hoped that by letting successive generations of AI agents loose on a series of

logical puzzle games a thinking creature would

emerge. The ultimate goal was to create an AI that could think for itself, at

which point it was ready to be uploaded into a physical robot body and released to

the wild.

However there is trouble in paradise. The mainframe in which the simulation is hosted is slowly failing, and in an unexpected twist the host program that runs the simulation has also become intelligent, and isn't keen on ending it all.

It's an unusually elaborate set-up for a puzzle game, but as with

The Witness the developers decided to use the puzzles to make a

series of philosophical points about perception, the nature of life, free will

etc. The game also poses a bunch of questions. Is this robot

thing us? Is humanity just a collection of DNA, or something else?

Given that the human body is a mass of cells acting in concert,

are we even us? If we can't live forever, can we at least project something of ourselves into the future?

In the hands of lesser developers

Talos could have been a pretentious, humourless bore. The backstory could have come across as a ridiculously OTT attempt to make the act of

putting boxes on top of pressure plates seem meaningful, but the voice acting

and writing sells it, and the story is helped along by some goofy humour. That's one thing that separates it from The Witness. It has humour.

There are only a couple of speaking parts - the seemingly-benign supreme being

Elohim, and the deceased human scientist Alexandra Drennan - but in both cases

I felt that the voice acting sold the roles. Drennan in particular had some of

the wonders-of-the-cosmos about her without being sappy.

You get a trophy for listening to all of her time capsules, and I felt sad

when the trophy notification popped up, because it meant she was gone. The first and

only time I have felt sad at getting a PlayStation trophy.

Incidentally I played The Talos Principle on the PlayStation 4.

The performance is unusually choppy, which is odd given that the environments

are very simple, but then again it was released in the first year of the

console's life, so perhaps Croteam were still learning the ropes.

You can mostly ignore the story, in which case it's still fun to play. The difficulty level is

finely-judged. I'll explain the gameplay. You're a robot:

You can pick things up and jump, but it's not a platform game. You use objects

to surmount the puzzles rather than clever jumping, although there are a

couple of puzzles that require you to dodge around explosive mines. These tend

to be the most nerve-wracking bits of the game, because for the most part

Talos is an ambient experience. You can foul up an arena, but

there are no penalties for resetting it. The soundtrack is lovely. The maps

are low-detail but the lighting is nice.

And then suddenly you mess up and beep-beep-beep-BOOM! a mine leaps at you and

kills you. It only happens a couple of times but it's disconcerting.

Talos is one of those games that gives you a palette of devices

and complications and then explores the way they can interact. Early on you

learn to use jammers to disable mines:

Later on you put boxes on top of pressure plates in order to open

doors, but you learn that you can put jammers on the plates instead, thus

allowing you to use a jammer to open two doors at once - the first door

with the plate and the second door by jamming it. A lot of the puzzles revolve

around efficiency. I often found myself solving most of a level only to run

out of tools before the final door, so I had to go back and work out how to

make my solution more efficient.

Some doors require that you channel beams with a connector from a power source

to a plug:

In that puzzle I've had to put the connector on a box, because otherwise

the two beams would intersect. Later on there are fans that can be used to

lift boxes up into the air, thus giving the connector a bigger field of view:

And in the shot above I've put a connector on top of a wall. This illustrates the

game's major strength, which is that I often solved puzzles in a way that

looked wrong, but the game kept going. As long as the solution works the game

will let you carry on. I can't tell if it's the result of extensive playtesting or just plain luck, but... well, luck is a skill, isn't it? Napoleon used to ask his generals if they were lucky. Admittedly he lost, and then lost again, but the point still stands.

The most unusual mechanism is the recorder, which records your actions and

plays them back with a translucent robot double:

The clone creates insubstantial-but-functional copies of world objects, and in

general the puzzles that involve the clone are the hardest in the game. You have to project your mind through time and space in order to solve them. Towards the end Talos gives you a portable

platform as well, but that element feels underutilised.

The Witness (2016)

Talos is often compared with The Witness, which was in development at the same time but didn't come out for another two years. The Witness has nicer lighting, although it's static - Talos has wind - and the puzzles are often fiendishly clever, but it felt sterile and I got tired of it.

Against you, there are mines that move in preset paths but seek you out if you get

too close - you can't dodge them at that point - and broken mines that merely

get in the way. And miniguns that shoot you if you move into their field of

view.

That's about it for gameplay elements, but it's a versatile palette that

sustains three sets of seven levels plus half a dozen bonus levels and some

extra bits.

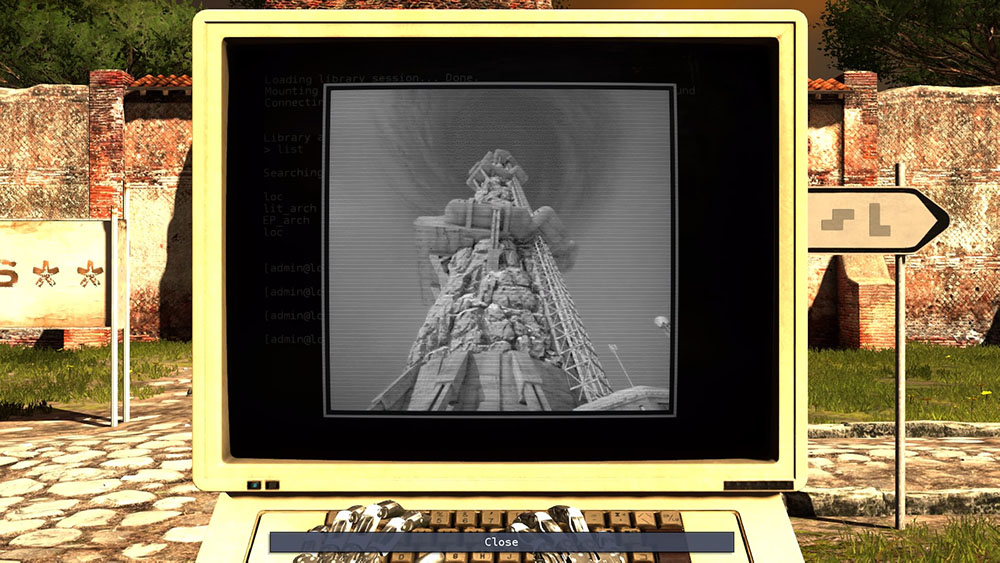

Why are you doing all this? The game is divided into a series of worlds, each

of which contains a bunch of puzzle arenas. At the end of each arena there's a

reward - a sigil, essentially a Tetris piece - and once you have enough sigils

you can unlock the next arena. There's also a giant tower, but you're not

supposed to climb it. Elohim said so. Instead he wants you to solve all the puzzles and run through a door, where you will be granted eternal life, although it's obvious that something's fishy.

As mentioned in the text you have to jump, but The Talos Principle

isn't a reaction-based platform game. As long as you can see these

footprints you'll make the jump.

There are some more mechanics. You can unlock helper robots that will give you

hints, but by the time you do it's largely pointless. Each map also has a

bunch of hidden stars, which unlock a special ending. Some of the stars are

hidden in such a way that you have to break out of the puzzles in order to get

them, e.g.:

The purple forcefields confiscate puzzle items, but they don't stop beams.

Is the gameplay any good? I have a wary relationship with puzzle games. For

all its clever design The Witness often irritated me. After

finishing a difficult puzzle I frequently felt drained and worn instead of

entertained. I didn't feel as if I had applied myself or worked something out.

Instead I felt as if I was just tracing lines back and forth on a grid for ten minutes until

they looked right.

Some of the puzzles were great - the audio puzzles in the jungle area stood

out, because I have a musical bent and finished them in no time - but there

were too many trace-the-line grids. Perhaps it's personal taste. I didn't get

along with them. Talos is occasionally frustrating as well,

because a few puzzles involve assembling sigils into a coherent whole, which

isn't a million miles from the trace-the-line gameplay of The Witness:

There are a few rules of thumb but I felt as if I was just moving blocks

around randomly. Perhaps spatial reasoning is the key thing that separates us

from lesser forms of life, but it doesn't feel clever. Furthermore if I wanted to test my spatial reasoning in an entertaining way, why not play almost any other video game ever made? R-Type, for example, or... I don't know, Wario Ware?

It's a shame because the rest of the game is finely-balanced. Often I was

baffled by a puzzle until I came back to it later on, at which point something

clicked in my mind, as if I had been processing it subconsciously. The game

even makes reference to this:

Outside the context of the sigil puzzles Talos is tough-but-fair, and at least until the

recorder came along I felt I had a handle on the puzzles, in which case

the fun came from implementing the solution rather than bashing my head

against a wall.

It reminded me a bit of Pete Cooke's

Tower of Babel, a 1990 puzzle game for the 16-bit computers that is now sadly obscure. In

that game you controlled a trio of robots that each had a special action, and

by programming them to move in concert you solved a series of 3D puzzles. I

remember reaching a point where I could solve the levels in just a couple of

tries, and from what I remember I managed to finish it.

I finished Talos as well. There came a point where the game

clicked, and I got the hang of the mechanics. The late-game introduction of a

platform did very little to make things more difficult, and I was only thrown

by the final level's time limit, and even then I enjoyed it because the last

level feels epic. I don't want to spoil things but it delivered a

satisfying, bitter-sweet emotional payoff. That's what separates

Talos from e.g. Antichamber, e.g. it's not just a

mindbending series of puzzles, it has a story.

Bad stuff? One of the optional puzzles is obtuse to the point of insanity, and

requires that you use your mobile phone to decode a QR code and then make a

mental leap. It's a one-off that appears early in the game, so perhaps the

developers decided not to go down that path again. The rest of the optional

puzzles are mostly tough but fair.

The fact that you can put boxes on top of

mines and ride them around without dying isn't obvious, although I worked it

out eventually; the fact that you can ride around on top of mines and not get shot by

guns that can clearly see you is less obvious.

The presence of miniguns as puzzle elements feels off, as if the team were

stuck with reusing assets from Serious Sam. Miniguns feel out of place

in a philosophical puzzle game, but that's a minor quibble. As mentioned the

performance on PS4 is all over the place. I'm not a frame rate snob, but

sometimes it was downright jerky.

DLC? Ignoring the novelty DLC, there's a set of block puzzles that were released as The Sigils of Elohim,

a free teaser for the game. I wasn't keen on the block puzzles so I haven't

tried it. You can carry over some of the stars you earn into the main game,

but the rewards are trivial. There was also an extensive mission pack,

Road to Gehenna, which has more puzzles and a separate storyline. The puzzles are apparently a lot

harder. I had a go at the first one but gave up after fifteen minutes. The

problem is that Talos is finely-balanced - it never gets

frustratingly hard - but pushing the difficulty up ruins that. Perhaps

Gehenna is a hidden gem. I don't know. I'll come back to it one

day.

The key thing is price. I can't tell how long I played Talos, but

£29.99 feels steep. It doesn't really have any replay value. The soundtrack is

nice but very low-key. At £15.99 however (with Gehenna) it's terrific.

I got it for £5.99, which is incredible value, albeit that if you don't have a PlayStation you need to

factor in the cost of the console on top of that.

The Talos Principle was officially released as a digital download

only, but as with

Gris there was a limited-run physical release by Special Reserve Games, but

only for the Nintendo Switch. In fact it was released only a few weeks ago,

back in June. The box had a reversible cover and a little booklet. I say

had because, inevitably, it sold out the moment it was announced.

Why Switch? Are Switch cartridges cheaper to make than Blu-Ray discs? Do

publishers have to pay a tonne of cash to Sony if they want to release

something for the PlayStation 4? Who knows. In any case that's all I have to say about The Talos Principle, goodbye.