Several years ago I had a look at Adox CMS 20, a slow-speed lith film. I began the roll in Milan and ended it in Shoreditch, where it ran out. Shoreditch and its mental environs are of course infamous for being trendy sixteen years ago, but trendy in an ironic way. Back then I mingled tangentially with some of its people. They meant no harm. Can you mingle tangentially? That's a bad phrase, I'll have to rewrite that bit. It will be swept away, everything will be swept away, but for now it remains. Enjoy it while it is still there.

I remember a fanzine called Shoreditch Twat, which mocked the culture of Shoreditch whilst simultaneously being part of the very culture that it mocked, which is ironic if you think about it.

Nowadays Shoreditch is a kind of digital hub, although as with all of the rest of London it's a thin shell lying on top of property. It's just up the road from Liverpool Street station, and the developers are on their way, as they have always been and will be. It was fields a long time ago, one day it will be a thin later of concrete dust underneath something else.

My pet theory is that Future London will be just a lot of solid concrete blocks. Not functioning buildings with doors and windows and water pipes, but solid concrete blocks. Already large chunks of London are unoccupied. The buildings are owned as investment vehicles rather than dwellings or businesses. Why not simply build empty shells instead? Hollow concrete shells with no doors or windows, just metal bars inside to stop the walls from collapsing inwards, to stop people from breaking in and squatting. They would be gigantic blocks of currency.

No-one would be harmed, because no-one lives in London anyway. There are precious few remaining businesses, and they could easily migrate to the internet. Without people, London could be simplified immensely; there would still be access roads so that investors can monitor their property portfolio, but there would be no need for cables or sewage, no need for restaurants or public transport, no need for petrol stations or drains. In my dream Future London will resemble an early 3D video game, just solid blocks in a grid pattern separated by unmarked pathways.

London is divided lengthwise, widthwise, horizontally and vertically, by class and location and ethnicity and every which way. Men are forced by tradition to use the outside of the pavement; women are not permitted to stand up on the bus; the other four genders must wear special socks. Shoreditch is in North London, but it feels like a mutant outpost of South London.

The stereotype is that North London is hard and harsh, full of tourists and businesses and Clive Owen barking into a mobile phone, whereas South London is a throwback to the Victorian age, with old men and their whippets eating jellied eels, and there are no tube stations and everywhere there is a field with people drinking beer as if in an Ocean Colour Scene video. Yorkshire is in South London.

South London is kept safe from North London by the River Thames, which marks its northern and western borders and envelopes it in a big cosy hug.

Shoreditch is an amalgam of the two ideas. It has buildings and businesses, but there isn't a tube station; it has young middle-class white people, and sometimes they do eat jellied eels, but in an ironic way. I wandered for a while, taking artfully composed snapshots with my vintage 1960s Olympus Pen FT half-frame film camera, acting out of the part of an urban hipster whilst being uncomfortably aware that no matter how much I dressed or acted the part, I would never be one of them.

For the hipsters, Shoreditch is a rite of passage, a gap year holiday before going back to the real world of contracts and working hours arrangements. For them it was part of their trajectory, for me it was akin to the hidden island in the first level of Goldeneye on the N64, distant and shrouded in fog, and when you visit there are no items.

The cranes approach to sweep it away; they are right next door, and if they don't destroy it, the sunshine, wind, rain and weeds will.

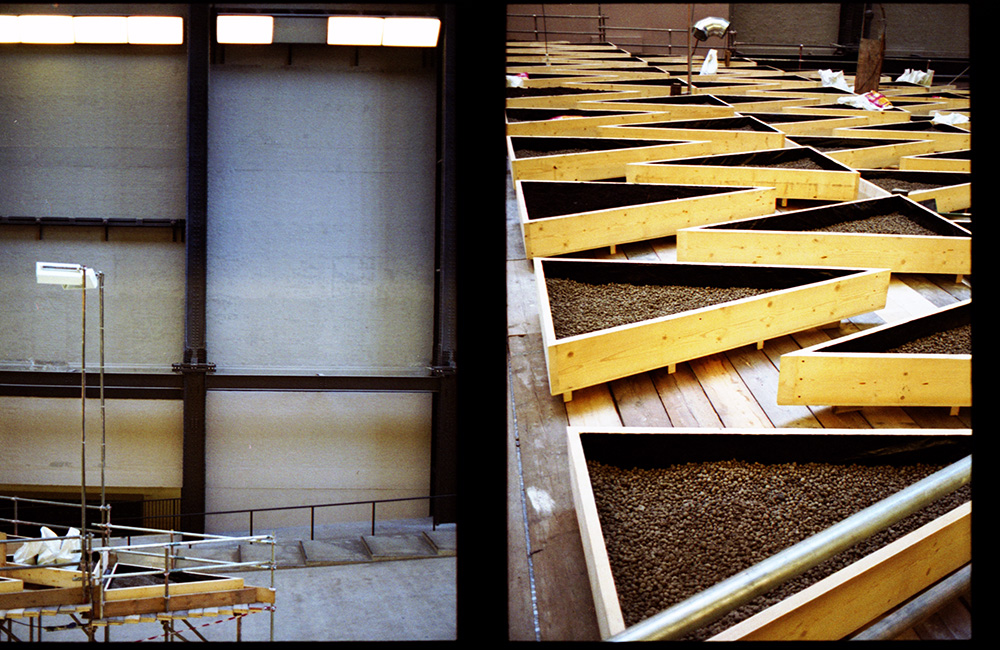

I turned away and walked off to the Tate Modern, which has a garden that resembles a vision of the future from a sci-fi film of the 1970s. Triangles were invented in the 1960s - it wasn't until computers came along that people could make three-sided polygons - and they still looked very modern in the 1970s.

No doubt once the plants have grown there will be a riot of colour, or alternatively the great weight of the plants will cause the scaffolding to collapse. Time will tell.

From 2000 to 2012 the turbine hall had thirteen major installations, all sponsored by Unilever; people remember Shibboleth (the big crack), Embankment (the big boxes), and Weather Report (the big sun), to a lesser extent How It Is (the big dark box). All paid for by sales of Pot Noodle. None of them have been disasters and no-one has died as a result of them - at least one person has died at the Tate Modern, falling from a balcony - but there's always a first time.